Today’s largest fires behave in surprising ways. In the late nineteen-nineties, a few scientists began inspecting satellite images of unusual clouds over Australia and elsewhere; the meteorologist Michael Fromm speculated that they could be connected to the convective force of giant wildfires below them. Eventually, the researchers confirmed that particularly powerful wildfires could cause not just pyrocumulus clouds but vast firestorms called pyrocumulonimbus columns. Created by the flames at ground level, the columns are tall enough to generate lightning, and their air currents are so strong that they can punch particles of smoke into the stratosphere, where commercial jets typically cruise. “There were some who literally laughed when we tried to tell them what we thought was going on,” Fromm told me. Skeptics believed that “if you saw aerosols in the stratosphere it had to be a volcano.” Read the rest here.

Photo by Joshua Dudley Greer

The New Yorker: Dirt-Road America

At the heart of the Ozark National Forest, near the Wolf Pen and Estep creeks, is a town called Oark, with a population of just more than three hundred. Oark’s general store, which opened in 1890, is situated where five county roads meet. You can buy a piece of buttermilk pie or a pack of cigarettes to smoke on the large front porch next to the ice machine; the cell service is unreliable, but guns are welcome, as long as they stay holstered. On a recent summer morning, the line cook stirred a skillet of flour gravy while Sam Correro tucked into a plate of eggs. “Have you seen any TransAmerica Trail riders come through here?” he asked the waitress, Bobbie Warren.

“Oh, yeah!” Warren said. “Every week.”

“That’s good,” Correro said, in a Mississippi drawl. “I’m the one that made the trail.”

For forty years, Correro has been riding a motorcycle through towns like Oark, stitching together a continuous pathway of dirt roads. Correro’s trail is not straightforward. Winding through America’s countryside, it largely avoids pavement, cities, and highways; instead of skipping flyover country, it goes through it as slowly as possible. No algorithm would advise you to take Correro’s route through the back of beyond. Read the rest here

illustration by Christelle Enault

The New Yorker: A Day in the Life of a Tree

Reporting this story involved obtaining my first research permit, which allowed me to install a fascinating instrument to the truck of a gigantic London plane tree in Prospect park called a dendrometer. It allowed me to see, minute to minute, the changes in the tree’s growth over the course of a day, week and month over the spring and try to understand the environmental factors that influenced it. I chose one day in particular to write about, which just so happened to coincide with a stunning thunderstorm in the evening.

One morning earlier this summer, the sun rose over Brooklyn’s Prospect Park Lake. It was 5:28 a.m., and a black-crowned night heron hunched into its pale-gray wings. Three minutes later, the trunk of a nearby London plane tree expanded, growing in circumference by five-eighths of a millimetre. Not long afterward, a fish splashed in the lake, and the tree shrunk by a quarter of a millimetre. Two bullfrogs erupted in baritone harmony; the tree expanded. The Earth turned imperceptibly, the sky took on a violet hue, and a soft rain fell. Then the rain stopped, and the sun emerged to touch the uppermost canopy of the tree. Its trunk contracted by a millimetre. Then it rested, neither expanding or contracting, content, it seemed, to be an amphitheatre for the birds. Read the rest here

Lane Skelton/RADWood

The New Yorker: The Fight for the Right to Drive

In March, 2018, General Motors announced that it would invest a hundred million dollars in a new car called the Cruise AV. On the outside, the Cruise resembles an ordinary car. But, on the inside, it’s what the automotive industry calls a “level five” autonomous vehicle: a car with no steering wheel, gas pedal, or human-operated brake. Ford, too, plans to release a car without a steering wheel, by 2021; Navya, a French company, already produces level-five shuttles and taxis, and has partnered with cities such as Luxembourg City and Abu Dhabi. Silicon Valley futurists and many Detroit executives see such cars as the inevitable future of driving. By taking people out of the driver’s seat, they aim to make travelling by automobile as safe as flying in a plane.

Last fall, the Philadelphia Navy Yard hosted Radwood, a car meet-up with a very different conception of the automotive future. The only cars allowed at Radwood are ones manufactured between 1980 and 2000. When I visited, early one morning, people had gathered around a red 1991 Volvo GL. The car was well worn from thousands of school drop-offs and soccer practices; its cracked leather driver’s seat still showed the gentle indent of its owner’s behind. Its most advanced technological feature was cruise control. Still, its hood was proudly propped open, in normcore glory. Speakers blasted the Talking Heads’ 1980 hit “Once in a Lifetime,” while, nearby, a man dressed in a nineties-style pink-and-blue windbreaker jumpsuit posed for a photo before a Volkswagen Westfalia. Other attendees cooed over a faded teal-green Ford Taurus, a twenty-year-old Mitsubishi Lancer, and a rusting Volkswagen Rabbit—the mundane cars that, in the previous millennium, had roamed the automotive landscape. Read more here

Photo copyright: George Schaller

The New Yorker: Peter Matthiessen’s “The Snow Leopard” in the Age of Climate Change

In the autumn of 1973, the naturalist and writer Peter Matthiessen and the zoologist George Schaller set out on a gruelling trek into the Himalayas. They were headed toward the Dolpo region of the Tibetan plateau. Schaller wanted to study Himalayan blue sheep; Matthiessen hoped to see a snow leopard—a large, majestic cat with fur the color of smoke. Snow leopards, which belong to the genus Panthera, inhabit some of the highest mountain ranges in the world, and their camouflage is so perfectly tuned that they appear ethereal, as though made from storm clouds. Two of them feature on the Tibetan flag of independence, representing harmony between the temporal and spiritual planes.

For Matthiessen, a serious student of Zen Buddhism, the expedition wasn’t strictly scientific. It was also a pilgrimage during which he would seek to break “the burdensome armor of the ego,” perceiving his “true nature.” After it was published, in 1978—first, in part, in The New Yorker, then as a book—“The Snow Leopard,” his account of the trip, won two National Book Awards, becoming both a naturalist and a spiritual classic. It overflows with crystalline descriptions of animals and mountains: “The golden birds fall from the morning sun like blowing sparks that drop away and are extinguished in the dark,” Matthiessen writes. But it’s also an austere Buddhist memoir in which the snow leopard is as alluring and mysterious as enlightenment itself. Read the rest here

WaterFrame / Alamy

The New Yorker: The Strange and Gruesome Story of the Greenland Shark, the Longest-Living Vertebrate on Earth

Sometimes you hear about a story that you can't forget. Over two years ago I happened to meet a biologist who casually mentioned a colleague studying Greenland sharks, and how they had used the same technology that detectives used to solve a murder and discovered the animals had seemingly supernatural longevity. It took me since then to track the people and details. Read the story at newyorker.com

"Greenland sharks are among nature’s least elegant inventions. Lumpish, with stunted pectoral fins that they use for ponderously slow swimming in cold and dark Arctic waters, they have blunt snouts and gaping mouths that give them an unfortunate, dull-witted appearance. Many live with worm-like parasites that dangle repulsively from their corneas. They belong, appropriately enough, to the family Squalidae, and appear as willing to gorge on fresh halibut as on rotting polar-bear carcasses. Once widely hunted for their liver oil, today they are considered bycatch. For some fishermen, a biologist recently told me, netting a Greenland shark is about as welcome as stepping in dog poop.

And yet the species has an undeniable magnetism. It is among the world’s largest predatory sharks, growing up to eighteen feet in length, but also among its most elusive. Its life history is a black box, one that researchers have spent decades trying in vain to peer inside..."

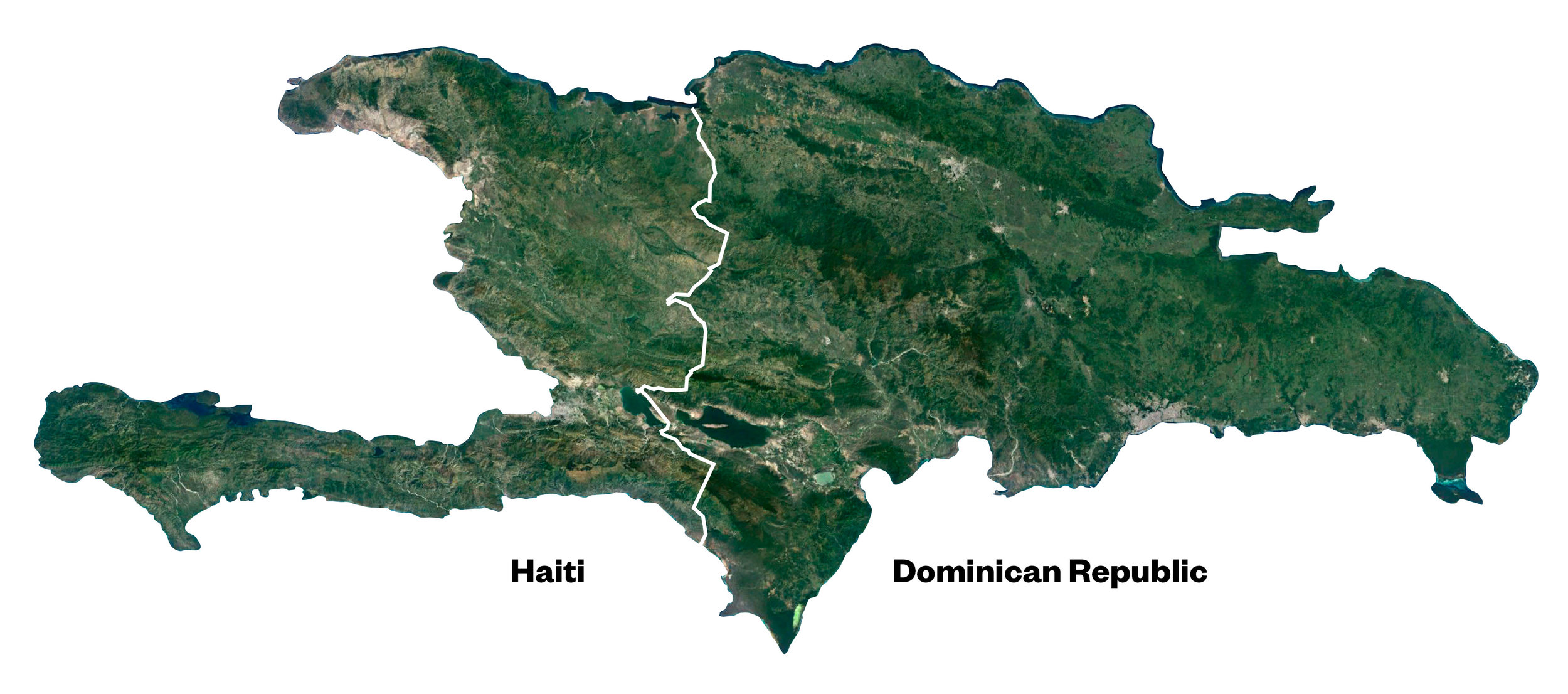

VICE: The world’s favorite disaster story: One of the most repeated facts about Haiti is a lie

When the geologist Peter Wampler first went to Haiti, in 2007, he didn’t expect to see many trees. He had heard that the country had as little as 2 percent tree cover, a problem that exacerbated drought, flooding and erosion. As a specialist in groundwater issues, Wampler knew that deforestation also contributed to poor water quality; trees help to lock in rich topsoil and act as a purifying filter, especially important in a country where about half of rural people do not have access to clean drinking water.

Haiti is frequently cited by the media, foreign governments and NGOs as one of the worst cases of deforestation in the world. Journalists describe the Caribbean nation’s landscape as “a moonscape,” “ravaged,” “naked,” “stripped” and “a man-made ecological disaster.” Deforestation has been relentlessly linked to Haiti’s entrenched poverty and political instability. David Brooks, the conservative New York Times columnist, once cited Haiti’s lack of trees as proof of a “complex web of progress-resistant cultural influences.” More recently, a Weather Channel meteorologist reporting on the advance of Hurricane Matthew made the absurd claim that Haiti’s deforestation was partly due to children eating the trees.

Few places in the world have as dismal a reputation. And as the recent destruction wrought by Hurricane Matthew shows, Haiti is tragically vulnerable to natural disasters. But as Wampler would discover, Haiti’s reputation as a deforested wasteland is based on myth more than fact — an example of how conservation and environmental agendas, often assumed to be rooted in science, can become entangled with narratives about race and culture that the powerful tell about the third world.

Read the rest at Vice

Nautilus: For Kids, Learning is Moving

Spatial cognition and memory have deeper importance to humans beyond daily survival: They inform our sense of self. Memories of the past are like pillars of our identity; we use them to build narratives about our lives. These stories inform our actions and choices, and create a framework for imagining our possible futures.

New research is shedding light on how the hippocampus develops in infancy and childhood, a time in which circuits are maturing, and new cells are firing and encoding space to create cognitive maps. It turns out that kids’ experiences—exploring environments, navigating space, self-locomotion—can influence how the hippocampus develops.

“This is very exciting because the maturation of the brain is often considered dependent on time and a genetic program,” says Alessio Travaglia, a researcher at New York University’s Center for Neural Science. “What we’re showing is that the development of the brain is not a program, it’s about experience. So if I am a baby in New York City or in a desert or a forest, the experiences I’m facing are different.”

News of such plasticity is both fascinating and alarming. It comes at a time when pediatricians are warning that children are given less time and freedom to play, and are more sedentary than ever before.

Read the rest at Nautilus

Illustration by Natalie Andrewson

The New Yorker: A Compass in a Haystack

Birds, turtles, dragonflies, sharks and elephants. So many animals travel long distances, in many cases thousands of miles, year after year. How do they find their way? I went to London to attend the tri-annual conference on animal navigation held by the Royal Institute of Navigation in April. Here's the story about the search for the animal compass and the scientists racing to prove two very different theories about how many animals navigate with such awesome precision across the planet.

Read the rest at newyorker.com

A Camp on the Shore of Victoria Land, originally published in the March 1913 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

Harper's: Postcard from The Frozen World

A visit to the American Museum of Natural History’s frozen-specimen collection, adapted from Resurrection Science, published in The Harper's Blog. "In an era of anthropogenic global warming, preserving life in man-made freezers is both prudent and ironic, not a solution in and of itself, but a last resort."

Read the rest at Harper's