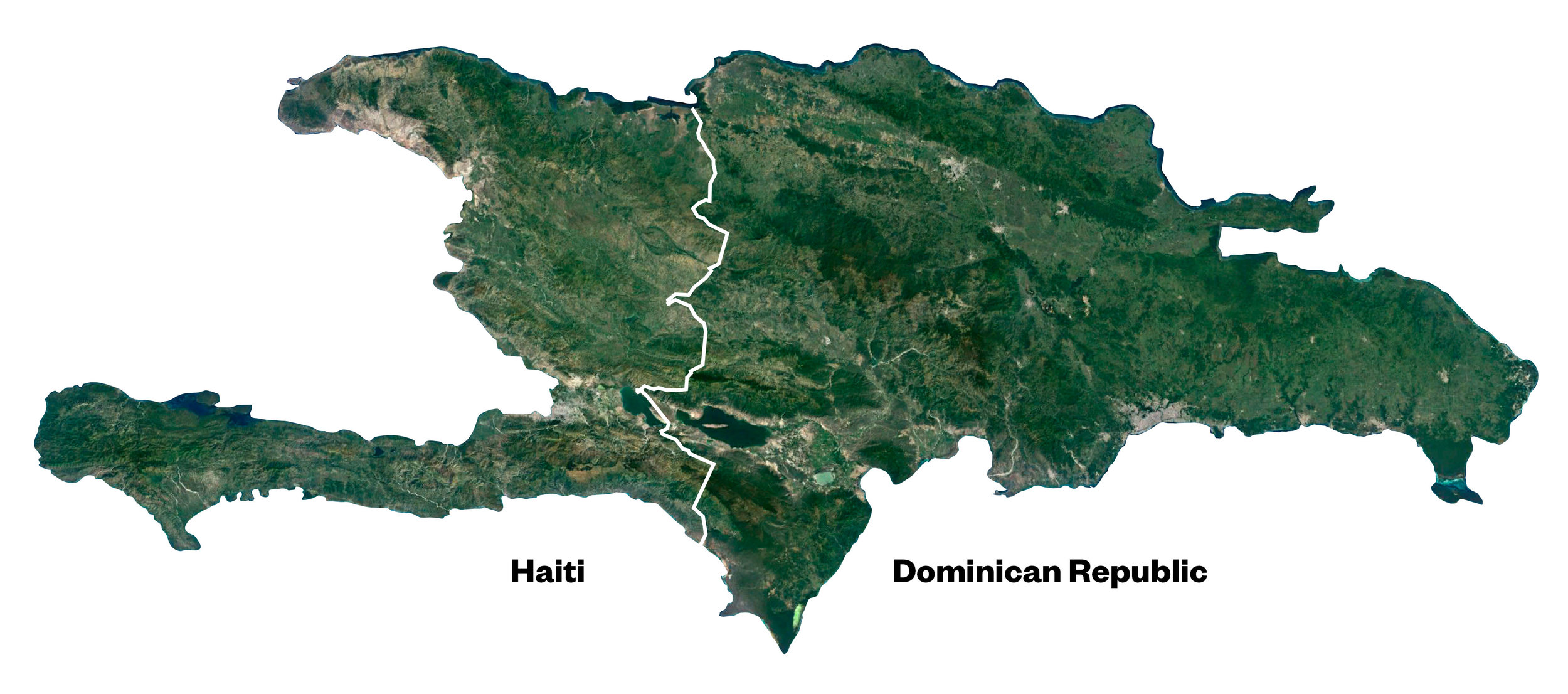

When the geologist Peter Wampler first went to Haiti, in 2007, he didn’t expect to see many trees. He had heard that the country had as little as 2 percent tree cover, a problem that exacerbated drought, flooding and erosion. As a specialist in groundwater issues, Wampler knew that deforestation also contributed to poor water quality; trees help to lock in rich topsoil and act as a purifying filter, especially important in a country where about half of rural people do not have access to clean drinking water.

Haiti is frequently cited by the media, foreign governments and NGOs as one of the worst cases of deforestation in the world. Journalists describe the Caribbean nation’s landscape as “a moonscape,” “ravaged,” “naked,” “stripped” and “a man-made ecological disaster.” Deforestation has been relentlessly linked to Haiti’s entrenched poverty and political instability. David Brooks, the conservative New York Times columnist, once cited Haiti’s lack of trees as proof of a “complex web of progress-resistant cultural influences.” More recently, a Weather Channel meteorologist reporting on the advance of Hurricane Matthew made the absurd claim that Haiti’s deforestation was partly due to children eating the trees.

Few places in the world have as dismal a reputation. And as the recent destruction wrought by Hurricane Matthew shows, Haiti is tragically vulnerable to natural disasters. But as Wampler would discover, Haiti’s reputation as a deforested wasteland is based on myth more than fact — an example of how conservation and environmental agendas, often assumed to be rooted in science, can become entangled with narratives about race and culture that the powerful tell about the third world.

Read the rest at Vice